The Reserve Bank of Australia and Treasury will prioritise research and experimentation on wholesale variants of any future digital central bank currency and defer deeper analysis of the case for any retail CBDC for years.

In a landmark speech at the Intersekt Festival in Melbourne yesterday Brad Jones, the RBA’s assistant governor for financial services explained the progress and research so far on this hot topic.

The RBA and Treasury also published a joint paper ‘Central Bank Digital Currency and the Future of Digital Money in Australia.’

The joint paper is “part stock take, part roadmap on a central bank digital currency and the future of digital money in Australia” Jones said.

This is the latest initiative to emerge from the RBA’s expanding work program on the future of money.

“With the strong endorsement of the Payments System Board, I can confirm that the RBA is making a strategic commitment to prioritise its work agenda on wholesale digital money and infrastructure – including wholesale CBDC – rather than retail CBDC” Jones said.

High-impact negotiation

masterclass

July 9 & 16, 2025

5:00pm - 8:30pm

This high-impact negotiation masterclass teaches practical strategies to help you succeed in challenging negotiations.

“At the present time, we assess the benefits to the economy as more promising, and the challenges less problematic, for a wholesale CBDC compared to a retail version.

“This recognises that unlike a retail CBDC that would be issued for use among the public, a wholesale CBDC would represent more an evolution than revolution in our monetary arrangements.

“It also recognises the stabilising role of central bank money in the settlement of wholesale market transactions, particularly in markets that are (or could be) systemically important – a point emphasised in international standards.

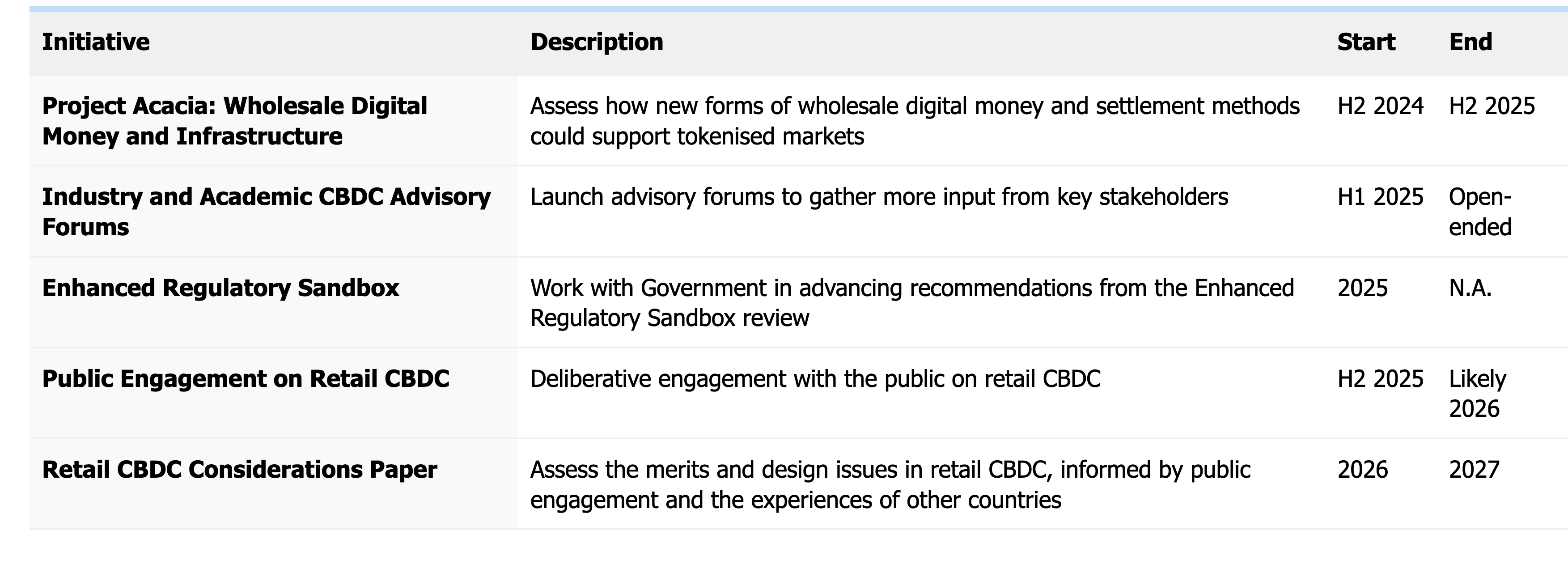

“Second, we are publicly committing to a three-year applied research program on the future of digital money in Australia. This has a number of elements” Jones said.

“Our most immediate priority is to launch a new project with industry on wholesale CBDC and tokenised commercial bank deposits.

“The focus will be on understanding how new ledger arrangements and concepts like ‘programmability’ and ‘atomic settlement’ in tokenised markets could unlock benefits for the Australian financial system and wider economy.

“We don’t have all the answers here, so look forward to engaging with industry partners who have an ability and appetite to innovate with the national interest in mind.

“Third, the view of the RBA and Treasury is that if a public policy case ever emerged in favour of issuing a retail CBDC, the Australian Government would be the ultimate decision authority and it would almost certainly require legislative change. This would also be in keeping with the recent international experience.

“In the case of a wholesale CBDC, the decision making and legislative implications would depend on how transformative the new arrangements were.

“But in either case, you should expect close engagement between the RBA, Treasury and government.”

After examining data on the state of digital money in Australia Jones asked: “if, as in many other advanced economies, digital money is already so dominant in Australia – mainly in the form of bank deposits - then what is the big deal about CBDC?”

A question not asked often enough.

“At one level, my sense is that much of the attention, if not intrigue, follows from CBDC connecting to deeply held views in parts of the community about the rights of citizens and the role and obligations of the state” Jones said.

“This includes issues of safety, privacy, freedom, sovereignty and even geopolitics – issues that put us squarely in political economy territory, which is not exactly the natural habitat of most central bankers .

“This might also explain why public debates over retail CBDC have been hotly contested in some parts of the world.”

As they soon will be in Australia.

In his section on “considerations” for a retail CBDC in Australia Jones touched on the number one hot button issue: Bank funding costs.

“Australia has a bank-based financial system. The share of bank funding sourced from domestic deposits has risen to around 60 per cent, and is higher again for small and regional banks that have limited (if any) access to wholesale markets.

“Should households place their liquid assets in a retail CBDC rather than bank deposits, banks would have to offer higher deposit rates and/or tap more volatile and costly sources of funding – costs that could be passed on to borrowers.”

“Banks could potentially compete harder for low-cost deposits by providing loans only to the very highest quality borrowers, but this would cut off credit access to otherwise creditworthy borrowers.

“And while central banks might consider offsetting a tightening in financial conditions with looser monetary policy, the idea that central banks should furnish banks with cheap loans as compensation for losing low-cost household deposits is more objectionable – it would raise a litany of other issues, moral hazard among them.”

The RBA and Treasury made clear they “are committed to reassessing the merits of a retail CBDC over time, with a follow up paper to be published in 2027.”