ANZ CEO Shayne Elliott

Since the euphoric banking days of the 1980s, ANZ’s financial performance has often been marked by spectacular bolt-from-the-blue write-downs as its strategic direction has flipped over and again from global expansion to a focus on domestic banking.

While the bank’s adventurous forays into global markets through the acquisition of volatile businesses such as Grindlays in 1984 were pitched to shareholders with promises of fat returns, they mostly ended as expensive disappointments.

Down the years, ANZ’s ability to surprise investors on the downside has much to do with the company’s inability to set a long term course for growth.

High-impact negotiation

masterclass

July 9 & 16, 2025

5:00pm - 8:30pm

This high-impact negotiation masterclass teaches practical strategies to help you succeed in challenging negotiations.

The last three chief executives of ANZ have spent their tenures largely undoing business models erected by their predecessors.

John McFarlane, whose decade-long reign at the bank ended in 2007, single-mindedly tried to “de-risk” the organisation by offloading offshore businesses that were acquired by Will Bailey (CEO in the 1980s) and later curated by another CEO, Don Mercer, for most of the 1990s.

McFarlane’s stated purpose was to refocus ANZ on its Trans-Tasman “home markets” and to reduce the cost base of the group.

A big part of that program was his decision in April 2000 to sell Grindlays, which at the time was mired in contingencies stemming from legal disputes with regulators and other Indian banks.

McFarlane’s work was almost completely undone by his successor Mike Smith who in 2008 began building a retail and wealth management network across China and Asia.

ANZ was reborn as Australia’s “international bank” under Smith’s so-called “super-regional strategy”, which once again diversified the commercial dimensions and risks of the company.

When he began eyeing opportunities for Indian expansion in 2012, Smith told a gathering of Indian business leaders in Melbourne that McFarlane’s decision to sell Grindlays was “a big mistake” for ANZ.

However, when Shayne Elliott took over from Smith in January 2016, the Australian financial press had already been carefully primed to anticipate a strategic unwind of most of Smith’s international banking gambit.

Elliott moved swiftly to scuttle Smith’s model. In October 2016 he announced ANZ was selling most of the retail banking and wealth businesses in Asia to the Development Bank of Singapore at a net loss of $265 million.

In June this year Elliott completed the dismantling of Smith’s regional dream after the last remaining consumer branches in Asia were shuttered in Japan.

“We lost our way a bit over the last 20 or 30 years and forgot what that core capability and excellence was around, and we started drifting into areas we probably had no right to be in such as retail. We have gone back to the basics approach,” he told the AFR in an interview earlier this year.

Shayne Elliott’s future at ANZ now hangs on the outcome of his effort to get the planned acquisition of Suncorp’s banking arm over the line at the Australian Competition Tribunal.

If the tribunal upholds the ACCC’s view that the merger is anti-competitive then Elliott’s position as CEO would become untenable.

However, if the bank gets the ACCC decision overturned his tenure might extend for several more years.

Elliott, who is now in the eighth year of his reign at the bank, has transformed the company through a weird brew of calculated organisational redesign and a string of mostly unfortunate operational accidents.

His reworking of the bank is reminiscent of McFarlane’s overhaul, which also put a big accent on shifting distribution to digital channels.

Consummation of the Suncorp transaction would fortify a key strategic theme of Elliott’s stewardship, which has always been to de-risk ANZ by refocusing the business on retail banking in its main home market and stripping the institutional bank of its riskier footings.

Joining Suncorp’s customer base to ANZ’s would also help fill holes in the Australian retail business caused by the bank’s failure to compete effectively in the domestic mortgage and deposits markets over a three-year period before and during the global pandemic.

While Elliott has sought to de-risk his bank by reining in much of its international presence, he is yet to demonstrate that ANZ can out-compete its peer banks and emerging rivals such as Macquarie in retail lending.

Under Elliott, ANZ has struggled to win market share in retail lending and deposits because the company’s technology has not been up to the job.

That’s a poor look for a bank striving to eliminate costs by repositioning itself as the country’s most agile digital lender and deposit-taker.

During the property boom of 2021, mortgage brokers deliberately steered clients away from ANZ because the bank was taking more than a month to approve loan applications.

It was the same story in 2019 when ANZ’s turnaround times ballooned, forcing thousands of its home borrowers to refinance with other lenders.

The upshot is that the bank now accounts for a smaller chunk of the Australian mortgage market than when Elliott took over in 2016.

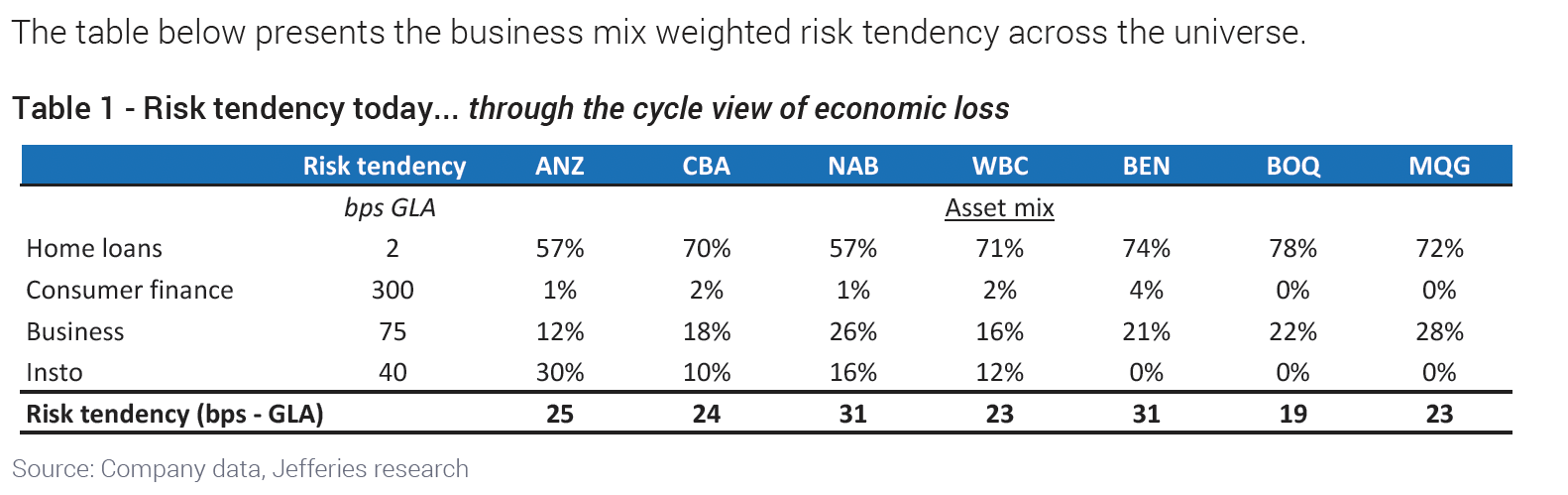

However, one of Australia’s leading banking observers – Jefferies senior analyst Matt Wilson – this week issued a research report showing how the combination of Elliott’s de-risking strategy and inadvertent market share losses could end up benefitting the company as the credit environment worsens.

In a report on the comparative credit risks of Australian banks titled

“Show Me, Don’t Tell Me”, Wilson suggests that ANZ’s shrinking mortgage book at the peak of the recent property boom means that it now owns the lowest-risk home loan business in the country alongside NAB.

Elliott’s reconfiguration of ANZ’s institutional bank has also resulted in a material de-risking of the division’s asset book away from corporates to sovereign credit risks.

In 2008 ANZ’s exposure to sovereign borrowers such as governments and central banks was only 3 per cent of total lending across the bank.

Today, it accounts for almost one quarter of the bank’s total credit risk exposure.

As Wilson highlights, the risk tendency on a loan to a highly-rated sovereign is effectively zero per cent over time.

Wilson concludes that ANZ is now better positioned than its peers to weather a sharp turn in the credit cycle.

“Might the outcome be that ANZ recognises the least and lowest bad debts in any emerging ‘mom & pop’ credit cycle?” Wilson asks in the report.

If Wilson is right, Elliott has positioned the bank – through a mix of design and accident – to ride the coming bad debt storm better than others.

Given ANZ’s history that would be no mean achievement.